Reloading: Get the Lead In!

- By Wheelwrite

-

0

Comments

Comments

- Last updated: 15/12/2016

Before we get into the tech talk let’s remind ourselves that lead is a toxic metal. Regular, un-gloved handling of it and its alloys can cause serious health issues as can the inhalation of the molten fumes. The use of either fine cotton or nitrile disposable gloves should be standard practice. The casting of molten lead should only be carried out in sheltered, well ventilated locations that are segregated from food handling areas.

Purely Lead

Within the realm of metallic cartridge ammunition the term lead bullet covers a veritable multitude of designs and material compositions. As a general rule the use of ‘pure lead’ is restricted to swaged pistol target bullets and some vintage calibres. These are primarily intended for low energy, high accuracy handgun applications in calibres such as .32 S&W Long and .38 Special, although a few specialist producers offer swaged ‘pure’ lead bullets in .45, .455 and other classic low velocity calibres. Soft alloys comprising lead and traces of antimony are drawn into lead wire and used to swage the bullets for .22 rimfire ammunition as well as some higher performance centrefire pistol calibres.

Under Pressure

The swaging process involves the cold compression of cut wire or cast lead slugs or billets inside shaped dies under high pressure, thereby ensuring that the bullet is accurately profiled and free from voids. The dies are dead size, that is, they produce a finished product of the required dimensions. In most swaging processes a bleed hole is used, allowing excess material to be extruded through a small vent in the die. This waste extrusion is known as sprue. A bleed die is generally designed with a two-piece profile body shaped to the outline of the bullet and with a stepped feature at the position of the bullet base. A piston is driven into the body, compressing the lead, its travel limited by the step in the body.

The specialist, alternative use of closed swaging dies requires extremely accurate pre-measurement of the slug or billet, but permits the use of much greater pressures and the resultant creation of extremely precise bullet definition. These dies do not always have an internal step to control the piston travel; rather they are limited by the stroke of the press in which the dies are located. Similar multi-stage designs can also be used to locate lead cores into gilding metal cases to form jacketed bullets

Swaged lead bullets generally have plain surfaces devoid of annular rings in which lubricant could be placed. Instead they are often finished by being tumbled in a warm mix of solvent based lubricant.

Cast of Thousands

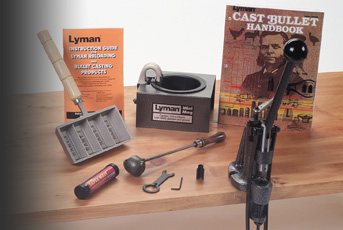

The vast majority of lead rifle and pistol bullets are produced by a casting process. A molten alloy of lead, antimony, tin and sometimes other trace metals in various ratios is poured into mould blocks, allowed to cool and then ejected. Several ‘standard’ alloy mixes are used, one of the oldest and most popular amongst hand loaders being ‘Lyman #2’, a brew comprising 90% lead and 5% each of tin and antimony.

Most non-commercial moulds are produced with 1, 2 or 4 cavities. The aluminium or steel moulds being made from two mirrored halves in the form of jaws. This two-part design easily allows for the inclusion of annular rings for both lubrication and crimping purposes. A hinged, sliding plate is positioned across the top of the mould, forming the bullet base and designed to cut the sprue from the bullet once it has cooled. In commercial production a gang mould can have many cavities, up to 20 or more.

Unlike swaging dies, moulds are produced to ‘oversize’ dimensions in order to take account of the shrinkage of the cooling alloy material. As the shrinkage of lead alloys varies with the composition of the mix, many mould manufacturers design their products to suit the default Lyman #2 mix. Nonetheless, the as-cast dimensions are often inconsistent due to variations in mould temperature and actual alloy composition. The profile is also less well defined than a swaged product, as the quality of the form is dependent upon the total evacuation of air from the mould cavity. The bullet may also contain small air bubbles or impurities that have not been fluxed from the melt.

Experienced home casters often ‘throw’ their cast bullets into cold water. This process causes rapid surface cooling which in turn increases the surface hardness.

Swage Finished Castings

In order to produce a consistent calibre diameter, smooth bearing surface and add lubricant to the annular rings, most cast bullets are then partially swaged. The process is known as lube sizing. The bullet is forced through a sizing ring that contains a pressure fed supply of wax-like lubricant. Plain (non-grooved) types are often rolled in lube after this process. A further enhancement that can be applied is to extend their performance range is the addition of a gas check. This is a gilding metal cup crimped to the base of the cast bullet as part of the sizing process.

Hard Work

In simple terms, the harder the lead bullet, the harder and faster it can be driven without loss of performance. For a given profile, alloy composition and firearm design there is a point at which the bullet will react adversely to the thermal effects of the burning propellant, the acceleration forces of firing and the engraving torque applied by the rifling.

The higher and more sustained temperatures generated by the use of double-based propellants will cause early base melt of soft alloy bullets, which is obviated by the addition of a gas check. As firing pressures increase so the mechanical deformation of the bullet will increase, creating higher contact pressures in the rifling which in turn will begin to induce the stripping of material, resulting in ‘leading’. Further lead fouling can be created by the failure of the bullet to properly engrave in the rifling due to the rate of acceleration in the bore. However, these are the upper limiting factors below which a wide span of acceptable performance often exists.

Pocket the Difference

A quick thumb through the Lyman loading manual will reveal that there are a surprisingly large number of calibres in which the use of a lead alloy or gas checked bullet is practical. The key factor is whether a lead bullet will deliver the performance you require. For most legitimate hunting purposes a jacketed-type is likely to be the best option, similarly with long range target shooting that requires the maximum ballistic performance from the calibre. However, for most other applications the potential savings are significant – providing that you are willing to spend a bit more time with the cleaning rods!