Reloading Basics: Fine Tuning

-

388

Comments

Comments

- Last updated: 14/02/2022

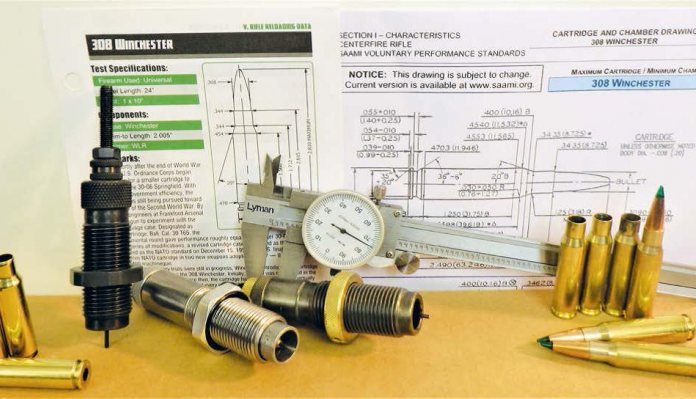

How you set up your resizing die can have a significant impact on the quality, safety and accuracy of your ammunition, plus effect brass life. Extra attention to the resizing process, and tuning it to your own particular gun, will help you get the very best from your ammunition, plus will have a positive effect on your group sizes as well.

Full-length resizing returns the entire case to its original factory dimensions. The case is squeezed back to its original diameter, the shoulder is pushed back and the neck is reduced in diameter. The reloaded cartridge can then be fired in any firearm of the appropriate calibre. Using a sizing plug on the decapping pin, a rifle full-length resizing die also work the inside of the case neck, forming it to the correct dimensions to grip a bullet.

Full-length resizing involves a lot of friction between the die and the brass, so the process requires the use of sizing lube. If you try to resize an unlubricated bottleneck case, you will find that it requires a lot of force to push it into the die and the case will then be stuck so firmly that the shell holder can actually rip the rim off when you try to extract it. This then requires a stuck case extraction kit to clear your die. You must lube bottleneck cases.

For a small number of cases, you can simply rub the tips of your fingers with the lube and then handle each case to apply a thin film of lubricant. For larger numbers of cases, a sprayapplied lube is more efficient. You just stand the cases in a row, give them a quick spray, then allow them to dry. The cases will be left coated with a thin film of lube. Alternatively, you can use a liquid lube applied on a pad. Do not leave any drops of lube on any cases, because the liquid will create dents in the brass during sizing.

Headspace is the distance from the bolt face to the part of the chamber that stops the forward movement of the cartridge when it is inserted into the chamber. For bottleneck cartridges, like .308, the part of the chamber that stops the forward movement of the cartridge is the angled portion that contacts the shoulder of the case.

The setting up of the die is particularly important to ensure that one particular feature of the brass gets properly formed, the shoulder. This part of the case is critical to proper headspace.

The difference between the chamber’s headspace and the cartridge headspace length determines the amount of room for movement the cartridge has in the chamber. If there is too little room (because the cartridge headspace length is too long for the chamber), the bolt will not close. Too much room (because the cartridge headspace length is too short) can result in inconsistent ignition, poor accuracy and short brass life, so it is important to get the cartridge headspace length right.

When setting up the full-length sizing die, the goal is to set it so that it pushes the case shoulder back just far enough so that the cartridge will reliably chamber and no further. The height of the die in the press will determine the distance that the shoulder is pushed back.

How do you measure the available room in the chamber? There are expensive tools available to help you do this very accurately, but there is also a simpler way of achieving a similar result. The simple option is to measure the headspace length of a case that was fired from the rifle. When a bottleneck cartridge is fired, the sides and neck expand, the shoulder blows out and the case stretches to take up all of the available headspace. To determine the right measurement for your resized cases, simply measure a case fired from your rifle and subtract the appropriate amount to leave just enough space in the chamber. For bolt action and single-shot rifles, a good place to start is with the cartridge headspace distance only 0.001″ to 0.003″ shorter than the available room in the chamber.

To set up the die, first, follow the instructions that came with it. Then, using a permanent marker, place a mark on the die to act as a reference point and help you to arrive at your final settings more efficiently.

Take a clean, lubed, fired case from your rifle, place it in the shell holder, run it through the sizing die, and measure the headspace length. It will probably be shorter than your target measurement, so you will need to back out the die to increase the headspace length of your sized cases to match your target measurement. This is where your reference mark comes in handy. Standard reloading dies have 14 threads per inch, so one complete turn of the die will move it vertically 0.071”. If you move the reference mark by the equivalent of 1 hour on a 12-hour clock-face, you would back out the die about 0.006”. This will allow you to make the adjustments you require.

Continue to adjust the die and run a case through until you reach your target case headspace length. Then, lock the die in place and run one more case through it to verify that you have it set properly. Your cartridge headspace distance is now set. It is important to remember that the above procedure assumes that you are using cases that were last fired out of the rifle for which you are reloading. You should then make up a dummy round (no powder or primer) and test it in your rifle to ensure that it chambers freely. If not, you might need to set the shoulder back a bit further.

It is critically important to set the shoulder of the case correctly. That shoulder acts as a gas seal, preventing high-temperature gases from leaking past the case and eroding your chamber.

If you simply set up the resizing die as per the instructions that came with it, you will probably be pushing the shoulder back further than is actually necessary for your rifle. The resulting cases will reload OK, chamber and fire (probably safely) in your rifle. They will also chamber and fire in any other gun of the appropriate calibre. If you adjust the resizing die as described above, properly sizing the case for your particular chamber, it will result in better accuracy, less case stretch when the round is fired and longer brass life.

You also achieve better accuracy through more consistent ignition. When the firing pin strikes the primer, the case is ‘knocked’ forward to take up all of the available headspace. Depending on your rifle, the primer might actually ignite instantly on impact with the firing pin (before the case moves), while the case is moving or when the shoulder bottoms out on the chamber and the case stops. The exact point of primer ignition might actually vary from shot to shot. With a lot of extra room for movement, this would be like firing a series of cartridges with varying overall lengths and varying amounts of bullet ‘jump’ from the case to the lands of the rifling, which results in reduced accuracy and less consistent groups.

When fired, the case will stretch to take up all of the extra room in the chamber. More headspace means more stretching, and more stretching means more frequent case trimming. Stretching also causes thinning of the case walls above the web and, as the case walls thin, the likelihood of a case failure increases. You will therefore get fewer reloads out of your brass.

The procedure described above is intended to tailor the cartridge headspace length to a particular rifle. If you are making ammo for multiple rifles you will either have to measure a fired cartridge from each rifle and set the case headspace length for the shortest chamber or set the case headspace length at or near the SAAMI minimum.

Experimenting with how much you resize your cases is a great way of finetuning your reloads to your own gun. Making your own ammunition is a good way to save money but when you start to make small changes to how you put each round together, you will find that it is also a way of getting the very best out of your gun in terms of accuracy.