Reloading: Humble Beginnings

- By Wheelwrite

-

0

Comments

Comments

- Last updated: 19/12/2016

It was 1975, in a Byfleet factory. An engineer started with a huge sheet of aluminium shaped like half a tear-drop, moving it around between two shaped steel wheels, making adjustments as he progressed. Slowly the floppy sheet morphed into an amazing work of art, the beginning of a wing for a rare Panther DeVille car. The skill was not only to create a 3D masterpiece but to arrive at the desired shape before the extent of the working hardened the metal to a point where it would split or crack.

Cold working metals has been around since the end of the stone age around 7500 years ago. The early users of copper, silver and gold soon discovered that it got harder as it was worked, ultimately becoming brittle. The use of heating and cooling to restore the original properties was understood by the early Egyptians, Greeks, Chinese and other civilisations as long ago as 5000 B.C. The process we now know as annealing. Metal alloys, that is, mixes of two or more elements, were in existence from the earliest days, but by accident rather than design. Brass, the alloy of most interest to us was often produced as the result of smelting ores which contained both copper and zinc (known as ‘natural alloys’), the two primary ingredients – together with traces of lead and iron. By 1000 B.C. the mix of zinc with copper to produce ‘gold’ metal was well understood.

The first breech-loaded cartridge cases were not made from brass or even copper but from thick, glued paper – hence the adopted term ‘Cartridge Paper’. These self-contained cartridges appeared early in the 19th century. They were essentially rolled paper tubes fitted with a thin copper central element that held a mercuric priming compound above a black powder charge and beneath the lead projectile. The priming compound was initiated by a fine needle that penetrated through the black powder charge, hence the term ‘needle-fire’. Then the metals arrived, thin copper cups containing a radially mounted internal primer, a striker or ‘pin’ positioned through the side of the cup, a black powder charge and a shaped bullet. The pin-fire cartridge was about as self contained as it is possible to get.

The introduction of the copper cup was the pivotal moment in modern cartridge development – it not only held all the components together, it acted as a pressure containment vessel – a gasket. Other copper cup variants were developed, the Benet system had a central primer assembly inserted through the top of the case and staked or crimped into place above the base… externally looking to the untrained eye like a rimfire. Then there was the true rimfire, familiar to us all in .22 LR cartridges. However, all of these designs shared one common flaw, they were intrinsically single use. It was the middle of the 18th century when patented cartridge designs by Clement Pottet and later primer designs by Col. Boxer paved the way for the metallic centrefire cartridge that we know today.

We already know that brass is an alloy of copper and zinc, sometimes with microscopic traces of iron, silicon, nickel, lead, tin, manganese or chromium. However, that mix or ratio can vary considerably. Traditional cartridge brass is an alloy of 30% zinc and 70% copper. (To put that into perspective, Gilding Metal, used as a common jacket material, is a brass alloy composed of just 5% zinc and 95% copper). The exception to this general rule is found with some designs of military brass, especially (but not exclusively) from the former Iron Curtain countries. Here a harder alloy is used, sometimes in concert with increased wall thickness thereby resulting in a reduced case capacity. This has little to do with cost and much to do with interior ballistics, together with the mechanical design/function of many military weapons. Colour is a good initial indicator of cartridge brass composition and condition, the yellow/gold colour of modern commercial examples contrasting sharply with the dark reddish browns of many military designs. Of interest is the fact that much pre-1960’s military ammo retained the annealing discolouration around the bottleneck, left intentionally by the makers to indicate that the process has actually been conducted. (A failure to anneal this area after forming was a common cause of separation and jamming!).

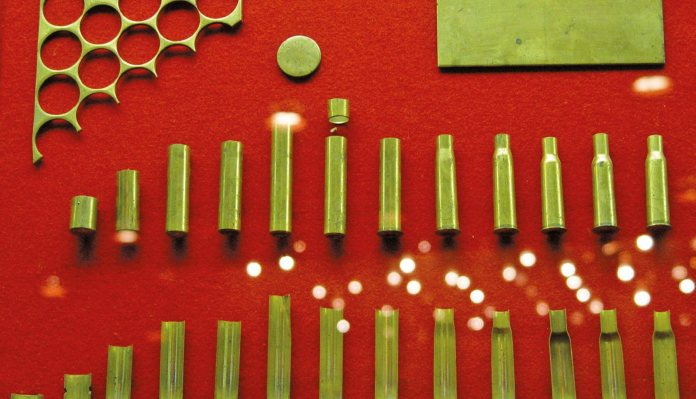

Modern brass cartridge case manufacture is variously described as a drawing or extrusion process. The traditional method being to punch thick circular billets from coiled brass strip and then, through a series of stamping (pressing) operations over metal forms, to create a closed tube of varying wall thickness. The extrusion version sees the brass billet forced at extreme pressure through a series of dies. At intervals through the process the material requires heat treatment (annealing) in order to restore its working properties.

This interim or ‘differential’ annealing processes being designed to create a range of hardness along the body of the case, the hardest area being the head and primer pocket. Once the tapered (thickness) wall of the cup is taller than needed for the finished case then the case is trimmed and the head and primer pocket are stamped on a tool called a bunter. This operation often taking place in conjunction with piercing the flash hole(s) and forming the rim. The work further hardens the head, pocket and rim areas. In some manufacturing processes the extractor rim undercut is turned or formed by a separate process. The bunter also adds the headstamp information – a requirement of CIP and SAAMI. Lastly the bottle neck (if present), is produced, locally annealed and the case chemically cleaned for packing or further processing such as nickel plating.

Whilst I have no means of verification Precision Shooting in its internet Benchrest pages has put some interesting stats into the public domain. They claim to compare Remington and Sako brass in 6MM BR. It was sent to a testing lab where scientific methods were used to measure hardness in Rockwell B. They quote the following results, although the size of the batches and their numbers were not disclosed. Remington: neck-13, shoulder-25, body average-55, primer pocket -61. Sako: neck-67, shoulder-65, body average-76, primer pocket-95. If correct, the figures illustrate why the life of one brand, under the same conditions, can be considerably different to that of another. In any event it makes the overwhelming case for the use of single brands/headstamps when reloading any batch of ammo.