Reloading Basics Bullets: Part 2

- Last updated: 19/11/2018

Once you have decided what type of bullet you are going to use, in terms of bullet construction and type, it is very important to match it to your particular gun. Usually, bullets are sold with most of the information you need shown on the box; calibre, diameter, weight, type etc. and this will generally be enough to ensure that they will work in your gun. One thing you will hardly ever see on the box, however, is the length of the bullet, and this is a vital factor when choosing the optimum bullets for your gun. This issue does make a vast difference to the performance of your finished ammo in your gun; so, is well worth some detailed consideration.

To get the very best performance from your gun, an often overlooked factor is the bullet length and its relationship to the rifling rate or ‘twist’ in your barrel. The rate of the twist is simply the number of inches of barrel over-which the rifling makes one complete turn, expressed for example as 1:10, which means that the rifling makes one turn in 10-inches of barrel. The rate of twist for your gun will be included in the documents that come with it or be available to find online. As a general rule, heavier bullets need a faster or ‘tighter’ twist rate to stabilise them. The principal behind the relationship between the rate of twist of the barrel and the weight of the bullets is this; heavier bullets, in a given calibre, are longer and so have more surface area in contact with the rifling. This means that they are affected differently by the rifling than the way lighter, shorter bullets are. Clearly, the entire length of a bullet is not in contact with the walls of the barrel, due to the taper towards the nose of almost all bullets; but, as the overall length of a bullet of a specific calibre is increased there is a general increase in the amount of surface area in contact with the barrel.

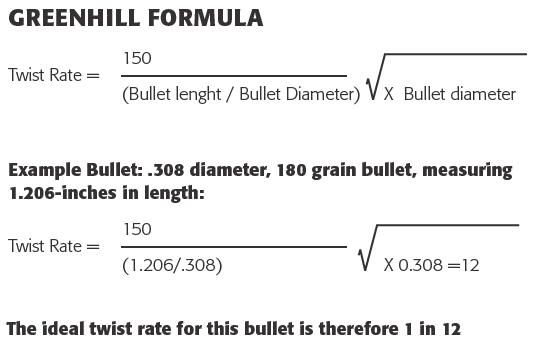

There is a way to calculate the rate of twist best suited to a particular bullet, using a calculation called the Greenhill formula, and this uses bullet length, rather than weight, as the variable factor. The calculation can also be used in reverse to calculate the best length of bullet for your gun and its rate of twist. All figures are in inches. To determine the best rate of twist, the formula divides 150 by the length of the bullet, expressed in calibres, and then multiplies the resulting number by the diameter of the bullet. The following example demonstrates how the calculation works: (See Greenhill Formula chart below.)

While a lot of theories do not always work in practice, this one does. It is the most effective and consistently reliable means of identifying the best bullet for a given gun. The biggest hurdle to overcome is actually getting the length of a given bullet without having to buy some first. Why bullet length does not get included on the packaging is a mystery; but, if you can get hold of this information, the calculation is quick and easy. One fantastic source of bullet lengths, as well as tons of other data for use when reloading, is the QuickLOAD software from JMS Arms, which lists literally thousands of bullet lengths. The same software can also be used to ‘design’ a load for your chosen bullet, allowing you to choose powders, charges etc. and calculate important stuff like pressure and velocity. More on QuickLOAD coming soon.

I have used this formula numerous times and on several different calibres. With only one exception, it has always allowed me to work out the bullet size that works the best in a given rifle, in terms of accuracy and consistency. The one exception is when I tried it on full wadcutter bullets in .357-calibre. The dimensions of the bullets generate worthless figures, but the bullets themselves are very accurate, one of the many anomalies or the reloading art! When I used the formula to work out the best bullet for my .308 Steyr, it showed that the best match to my gun would be a 190-grain bullet. This was a surprise, as I had been using a 145-grain bullet with acceptable results. Upping to various heavier bullets gradually, I ended up settling on a 180-grain PPU soft point with fantastic results. Coincidentally, the test target supplied with the rifle was produced using 190-grain bullets. I am not sure how long this formula has been around, but it certainly seems to have stood the test of time and still works well.

Reloading is a complicated art and keeping the variables in check is the key to success. This formula allows you to tick bullet size off the list of variables and find the best bullet for a particular gun. Despite having to run the calculation a few times, to get to a bullet length that best matches the twist of your barrel, and then finding a bullet of that precise length, it is a very useful and worthwhile tool. When you have found the right bullet, all you need to do is consult available reloading data, to find a suitable and safe powder charge for it. I definitely recommend that you give this a go, the results will optimise your bullet to rifle match and so improve the overall performance of your reloads. When you are starting reloading for the first time, it gives you a quick and easy way to start off with the right bullet.

Norman Clark Gunsmiths normanclarkgunsmith.co.uk

Henry Krank & Co henrykrank.com

JMS Arms jmsarms.com

1967 Spud Reloading Supplies 1967spud.com

Hannam’s Reloading Ltd hannamsreloading.com