Reloading Basics: Close inspection

- Last updated: 21/06/2023

When you reload your own ammunition, you want to know how it performs, and the two easiest things to assess are its accuracy and how well it feeds in your gun. You can also invest in a chronograph to measure the velocity of your loads. These are all good ways to evaluate how your ammunition performs, but taking a closer look at your fired brass can also give you a lot of useful information.

Shooters often overlook checking their fired brass, but if you know how to read the signs, then you can learn a lot, and maybe improve your ammunition. There are some signs you can read that have a bearing on the performance and the safety of your ammo, and most are related to issues that you can easily address.

The condition of the fired primers can be a very useful source of information. If the primers are loose in cases that have only been reloaded a couple of times, then this is a sign that your loads may be too hot. The excessive pressure stretches the brass around the primer pockets, ‘slackening’ them, and once the primer pocket is enlarged, the case is useless. In extreme cases, the primers can be blown through, with a blackened hole all the way through the primer cup. This is a sign of excessive pressure and a warning sign.

Sometimes, the primers can be completely flattened after firing, and although not as serious as blown primers, this is a sign that you should back off the powder charge a little.

There are also signs that indicate more mild overloads. If your rifle has a spring-loaded ejector, it can leave a shiny round mark on the case head. This is usually associated with brass that is too soft, but is also a pressure sign.

The higher the chamber pressure is, the more obvious the signs become. If the cases are sticking in the chamber, and are hard to extract, your reloads are excessively hot and should not be used. If you see scratches along the length of your cases, then that indicates that the brass is being dragged against the chamber wall during extraction. Cases can become so stuck that the extractor tears through the case rim, leaving a case jammed in the chamber. Loads that are this hot should not be used.

If you continue to use cases that are old, swollen, and excessively dirty, this can also cause them to stick in the chamber. The brass is so ‘exhausted’ that on firing it expands to the dimensions of the chamber and does not spring back down in size at all.

These occur when brass has been fired several times, as it becomes brittle due to the repeated heating and swelling that firing exposes it to. This is normal wear, not generally a sign of excessive pressure, and once you see cracks appearing, it is time to retire the entire batch of cases. It is possible to anneal the brass, a process which makes it softer and more malleable, but this requires specialist and expensive equipment, meaning it doesn’t make sense for your average reloader.

With straight-walled cases in mild calibres, like .38 special, the body may not split until after several firings, but high-pressure loads in .357 Magnum will often cause cases to split after just a few uses. Again, this is normal. Generally, split cases are not a sign of excessive chamber pressure.

Headspace is the distance from the bolt face to the part of the chamber that stops the round from moving forward. It is determined by the case design. For example, rimmed cases generally use the rim, a bottleneck case uses the shoulder, and a straight case uses the case mouth for headspacing. Excess headspace occurs when the chamber is too long, allowing the brass to stretch too much, which can cause anything from misfires to case separation.

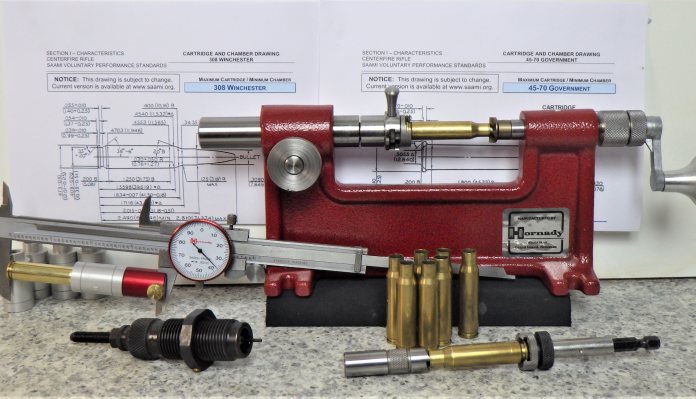

As a part of your case inspection, you should measure the length of your fired cases before and after resizing, to see how much you are pushing back, or ‘bumping’, the shoulder of your cases. If you are having to reduce the length of the cases significantly, trimming them so they will chamber correctly, this is a sign of excessive headspace. Cases that are stretching too much each time they are fired will often crack and separate around the base, just in front of the case head.

Another cause of case separation can be a case that is slightly too long, or improperly headspaced, causing the case mouth to enter the forcing cone of the barrel. When the round is fired, the bullet tries to take the mouth of the case with it, while the head of the case is stretching back towards the breech face.

High pressure doesn’t cause case separation alone, but it can cause problems if the gun has excess headspace. Case separation can be dangerous. It can also be hard to remove the front portion of the case from the chamber.

If you are having headspace issues, you can usually work around it by simply setting your sizing die back a little. When you size brass, the shoulder is pushed back. If you set your die so it sizes the case just enough to chamber, the shoulder won’t be worked as much.

Often careful load development can result in high-performing, accurate loads, but attempting to exceed the recommended velocities is not a good idea. This will generally result in excessive chamber pressures, as the published loads will have been very carefully developed and tested to ensure the pressures are safe. Even a published load can sometimes be too warm in some guns, due to variations in chamber and barrel dimensions. Keep within the recommended velocity limits, and remember to read your brass.